Dalibor

Opera from Bedrich Smetana – Theatre performance

Premiere planned: 17. 11. 2000, The National Theatre, Prague, Czech Republic

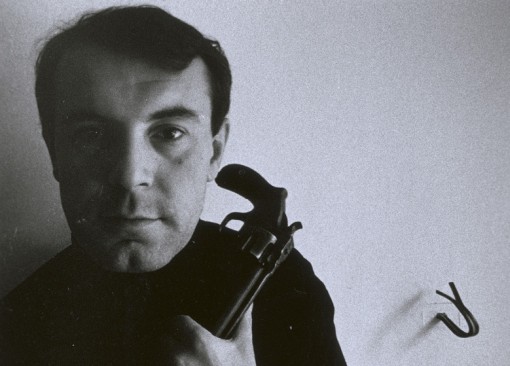

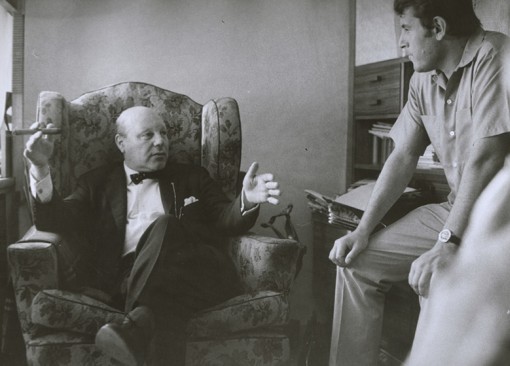

In 1998, Jiri Srstka (the contemporary director of The National Theatre) proposed producing Smetana’s opera “Dalibor” directed by Milos Forman. Forman was a fan of the opera, and agreed to direct. However, he insisted on a radical shortening of the libretto: he planned to skip the story of the lovers; the whole second act and also move one aria to a different part of the plot. Forman considered the old translation by Erwin Spindler (who translated the libretto from German, originally written by Josef Wenzig back in the 19th century) old-fashioned and not relatable to a contemporary audience. He hired actor and songwriter Jiri Suchy to rewrite the opera.

In order to communicate his intentions for the new performance Forman edited an older version of the “Dalibor” opera and sent it to Prague. The management of the National Theatre and Libor Pesek (the conductor of the performance) agreed to Forman’s concept.

In January 2000 the project was introduced at a press conference for the National Theatre. After the conference, there was a backlash from both experts and the non-professional public. The contemporary Artistic Director of the National Theatre was also against the changes to the opera because of the originals´ role in the national heritage. In the end, Forman decided to withdraw from the project before the start of rehearsals.

Milos Forman about the project:

- “When I had the opportunity to do ”Dalibor”, I decided to do this opera in the way I´d always wanted to see it as a student. I still recall at exactly which moment I would go out to smoke. I was always walking around the foyer during some of the acts, so I wanted to leave these parts out of my version completely. For instance, the whole second act seemed totally unnecessary to me. Escape from the prison tower is being planned, but then we see the escape almost immediately afterwards. Then I wanted to move Dalibor’s aria, which he sings right after he files the bars of his prison cell. At that moment, Dalibor could have just run away, but instead he starts to sing a wonderful ode to freedom, and he sings and sings until the guards realize what is going on and he is imprisoned again. I thought that for this beautiful song I had to find another, more logical moment.”

- “When I finished with the editing (I had done it quite brutally on my old tape recorder), the opera was 30 minutes shorter, but there was still one hour and forty five minutes of Smetana’s fabulous music there. I sent it back to Prague just to show my intentions. Immediately an answer came back from Libor Pesek, the conductor in charge of my production. He liked my plans and he was looking forward to the cooperation very much. But suddenly and unexpectedly a very sharp “no” was given by the Artistic Director of the National Theatre Opera. Up to that moment I had been dealing with his boss, Jiri Srstka, so maybe the Director of the Opera section felt unappreciated. Well, he said that such editing of Smetana’s work would be impossible, and that this jewel of Czech art couldn´t be sacrificed for the sake of modernity, etc.”

- “My reasoning was clear:

‘Oh please, come on, who nowadays does Shakespeare’s plays in the same way as Shakespeare wrote them? Absolutely no one.’

‘But this is not Shakespeare.’

‘Well, exactly. This is not even Shakespeare.’

‘Exactly! It is Smetana we are talking about!’

‘Well, you see then.’

‘Do whatever you want to with Shakespeare, but no one is going to touch our Smetana! Not even a single note will disappear!’

There wasn’t any other option than to give up on “Dalibor”.”

- “When I announced my decision to the General Director Srstka, he tried to save everything by making me an offer – a compromise. I could do whatever I desired with “Dalibor”, if the Artistic Director of the Opera section could release his own version of “Dalibor” at the same time. So, in the end, I realized that opera is not a fun game, and that I didn’t want to accept this challenge. I definitely couldn’t afford to duel with someone who was used to ruling the whole National Theatre and who could completely destroy me and my production one way or another.”

|