“Everything I did in my life I did because I wanted to win. The will to win belongs to my essential motivational powers. However, winning is quite exhausting so the next thing, which always comes to my mind, is this: Fine, I have won, but that’s not it. Next time it's going to be even harder."

Family

Milos Forman was born in 1932 into a teacher’s family in the small town of Caslav (Central Bohemian region). He was the youngest of three brothers. His father was a member of a resistance group against the Nazi occupation, and was arrested by the Gestapo when Milos was eight years old. Shortly afterwards, Forman’s mother was also arrested. This came about when a local grocery store owner named Havranek was arrested for not informing German officials about anti-Nazi leaflets that appeared in his store. When Havranek was interrogated he mentioned the names of twelve women (including Mrs. Formanova). All of these women were arrested.

Forman recalls: “We are really not sure what the Gestapo had done to Mr. Havranek, so that he mentioned those names in the end. He never returned from the interrogation. Most probably he had been tortured and in the end he committed suicide in his cell.” The Gestapo closed the unsolved case and the arrested women were released. “The only one who didn’t come back from prison was my mother, despite the fact that her name must have been mentioned by coincidence. We had been avoiding Havranek's shop on purpose.”

Forman learned the real reason for his mother’s imprisonment only after the war was over. Her release was revoked by a former foreman bricklayer from the Sudetenland who had worked on the construction of Forman’s family hotel long before the war. During the war this man made a successful career in the Gestapo. However, his reasoning for revenge is still a mystery. Mrs. Formanova died in Auschwitz 1st of March 1943. The same Gestapo officer sent Forman’s father to a concentration camp even though Mr. Forman had already served his sentence before the trial ended. He died in Buchenwald in May 1944.

“My parents were real patriots, and that was probably the reason why they died. Not until much later, when I was suddenly far from my homeland and its culture, far away from my family, when I was cut away from the land of my childhood, I realized I shared this strong feeling of affection for my country with them.” – Milos Forman

In the early 1960s, Milos Forman learned that Rudolf Forman was not his real father. Forman’s real father was a Jewish architect that his mother had met while working on the construction of the Forman’s hotel. His mother’s concentration camp cellmate passed this information to Forman. Forman’s mother told the woman and had made her promise to find Milos and tell him the truth. “I think my father never found out the truth. And if so, then he never indicated anything. He always treated me as if I was his own blood, his son. Rudolf Forman was my real father.”

Forman attempted to contact his alleged father in South America, but the elderly gentleman did not want to dig up the past. Nevertheless, he stays in touch with his children. It has been verified through DNA tests that he really was Forman’s father.

Wartime

For part of the war, Milos lived with his aunt Anna and uncle Boleslav in Nachod. Later he was taken in by the family of the director of the local gas company in Caslav named Mr. Hluchy.

“When I was traveling with my suitcase from family to family, I soon realized that the thing which really helps you in your life is not to cause trouble at all and to convince the others to become fond of you very quickly,” remembers Forman. Therefore, he tried to do his best at school and helped a lot in the households or shops of his well doers. “I had found out that to rebel against anything was unbelievable existential luxury I couldn’t afford. So I’ve grown up into a diplomat more than anything else,” he adds. Perhaps the loneliness of traveling with only a suitcase helped him in his future work.

Podebrady

After the war, Forman attended a boarding school for war orphans in Podebrady. He describes his school years as thus: “I was surprised by the amount of pupils of our boarding school who actually had their own mother and father. There were a few boys who had lost their parents during the war as I had but most of them were children of ministers, diplomats and the pre-war time elite and even of communist officials.” Political parties competed to donate money to establish a new school for boys who had lost their families during the war. Due to the large amount of these donations, the headmaster could afford to have the best teachers, and it became the best high school in the country. Both the new communist elite and the old capitalist elite would try to get their own children into the school with the war orphans. At school Forman received the best possible education and met his lifelong friends Ivan Passer (who would go on to become a filmmaker) and Vaclav Havel (who would later become President of the Czech Republic). Among his schoolmates were the Masin brothers. They were the sons of the anti-Nazi resistance hero Colonel Josef Masin, and later formed an anti-communist resistance group that operated in Czechoslovakia from 1951-1953.

After the communists took power in February 1948, Forman was accused of a misdeed– according to one of his teachers, he made fun of the communist party –and he had to finish his high school at another school in Prague.

Prague – the 1950s

The theatre has fascinated Forman since childhood. The first time he experienced the world of theatre was during the war. His older brother Pavel worked as a painter in a barnstormer’s group called The East Bohemian Light Opera Company. Forman describes his first encounter with the world of show business: “The backstage of the operetta company smelled nicely of a mixture of voluptuous femininity, cheap scents, violets, sweating bodies, roses, make-up, stiff laces being ironed, moth balls, alcoholic drinks, cookies, ballet shoes with sweaty tights and little skirts with a light scent of urine – and I immediately decided that this is the world I belong to.”

The only thing he didn’t know was what exactly he wanted to do in the theatre. “From the very beginning I was convinced I didn’t want to be an actor. I had noticed, that the male members of the ensemble were treated horribly backstage. But then an aging man burst into the dressing room. He seemed to be heat up, his jacket was crumpled and he was bolding, and yet all the beautiful women couldn’t take their eyes off him. He was apparently slightly drunk, but they were smiling at him and flirting, simply they were ready to do anything to make him falling for them. I would love this, that’s what I thought then. ‘Who is it?’ I asked my brother. ‘This one? He has directed it,’ Pavel answered. ‘And is he able?’ ‘Well, yea, able to booze, mostly.’ Apparently, my brother didn’t have the best opinion of the director, but I had my ideal for life.”

Forman took part in a local amateur group at the Na Kovarne Theatre. Then, in the 1950s, he founded an amateur theatre group with his schoolmates and staged a successful production of the Rag Ballad (1950). However, he didn’t pass the entrance exams to DAMU (the Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Arts, in Prague). The official reason was that he did not manage to perform “the fight for world peace” in his talent exams.

In order to avoid military service Forman applied to FAMU (the Film Faculty of the Academy of Arts). He was accepted and began to study screenwriting. “Now I understand that FAMU granted me the same comfort as my teachers – a chance to survive the Stalinist fury of the 1950s, which had been disrupting everybody and everything. And even better, we had really wonderful teachers, e.g. Milan Kundera or Milos. V. Kratochvil.”

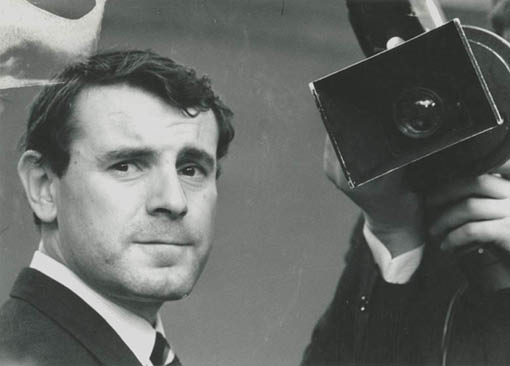

Artistic beginnings

During his second year of college, Milos Forman took part in an open competition to be the host of a film and filmmaking talk show for the newly established Czechoslovak Television. “I had the idea that such a job might be a good start for the career of a sports commentator, which seemed to me as the best job ever - being a sports commentator you only had to go to soccer and ice-hockey matches, were paid for it and you could even travel to the West!”

Forman got the job. This job involved familiarizing TV audiences (still very limited at that time) with the latest trends in both socialist and Western cinematography. Forman was even given a chance to be a sports commentator (his dream job). He recorded a five-minute commentary at an ice-hockey match at Prague’s Stvanice Stadium. “I tried my best, but no one from the sports section ever responded.”

Throughout his studies, Forman played minor roles in several Czech films. In 1956 he tried his hand at directing his first movie called Dedecek automobil (Old Man Motor Car / Grandpa Automobil, 1956). The director of the film, Alfred Radok, let him direct one of the crowd scenes. The following year he worked with Ivo Novak as co-author and assistant director on the film Stenata (Puppies) (1957). While making this film Forman met his first wife Jana Brejchova (who later became a famous Czech actress). They married soon after the shooting was over.

Radok asked Forman to work with him on the multi-media performance Laterna Magika (1958). This performance ran at the World Exhibition EXPO 58 in Brussels, and it became a great success worldwide. After their return to Prague, Radok asked Forman to help him with the next performance, called Laterna Magika II: Zájezdový program (Laterna Magica II: The Tour Programme) (1961). During pre-production Forman and his wife Jana Brejchova separated.

The 1960s

In the early 1960s, Forman bought his own movie camera in East Germany and began to shoot a documentary about the popular Prague theatre the Semafor with Ivan Passer and cameraman Miroslav Ondricek. While shooting the documentary, they came up with the idea for the film Konkurs (The Audition) (1963). Forman, Jiri Suchy, and Jiri Slitr (the artistic directors of the Semafor Theatre) organized a fake audition for a female singer and thousands of ambitious young girls turned up. The filmmakers made a stylized documentary about this audition. Forman cast Vera Kresadlova (his future second wife) whom he had met at a rock and roll concert in Prague in the role of a young singer. They were married in 1964.

Forman recalls: “When we got married, Vera’s belly was really enormous and it was growing more and more. The doctor said that Vera would have either some kind of a giant or twins. The only way how to find out was the X-ray, as there were no ultrasounds in those days, but Vera refused that.” It used to be custom that the father-to-be would be wait for the news from the hospital in a pub drinking with his friends. “A noble Dame of Czech theatre, Mrs. Stella Zazvorkova, gave a party in my honor. I was just sitting at the table and drinking with my friends, when they called me from the hospital. Vera gave birth to twins, Petr and Matej, and they all were alright…There is another Czech custom, which requires from the new father to eat a bowl full of hot lentils with a raw egg. The lentils symbolize money, and the father has to eat it all so that the family stays wealthy. Stella put the bowl in front of me and everybody started to make jokes and tease me. Stella took an egg and broke it and everybody got silent. That egg had two yolks in it.”

That year Forman shot his first feature film Cerný Petr (Black Peter, 1963). The screenplay was based on a short story by Jaroslav Papousek. After the film won the International Film Festival in Locarno, Milos Forman was able to visit the USA for the first time. However, it was his next film, Lasky jedné plavovlasky (Loves of a Blonde) (1965) that sparked his international career. The film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

This Academy Award nomination established Forman a famous European filmmaker, and sparked the famous Italian producer Carlo Ponti to invite Forman, Jaroslav Papousek, and Ivan Passer to Italy. Ponti wanted them to write a screenplay about a hunt for the last bear in the Tatra Mountains in Slovakia, but the trio did not want to make this film. The three filmmakers started working on other projects, and finally settled on a script about their own experience at a volunteer fireman’s ball in the little town of Vrchlabi in the Krkonose Mountains. This experience led them to the bitter comedy Hori, ma panenko (The Firemen’s Ball) (1967), which won Forman another Academy Award nomination.

New York

In 1967, Forman received permission to travel to the United States to make his first American film for Paramount Pictures. He had thousands of ideas (including a film adaptation of Franz Kafka’s novel Amerika (America), however the communist film authorities rejected these ideas.

During his stay in New York City, the hippie movement fascinated him. Forman and the French screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere saw a preview of the musical Hair and decided to make its film version. They couldn’t get the rights to the play, so they started writing the screenplay for Taking Off (1971).

In spring 1968, New York was turbulent city, overwhelmed with protests against the war in Vietnam. The filmmakers went to France in the hopes that Paris would be a more peaceful place to write a screenplay. However, the 1968 student revolt had just started and the streets were full of barricades. Forman suggested returning to Prague, which seemed quiet compared to New York or Paris. Unfortunately, Prague Spring, the historic attempt to modernize the communist regime was at its height. At the beginning of August they returned to France where they heard the news of the Warsaw Treaty troops invasion to Czechoslovakia. Forman’s friends managed to bring Forman’s wife Vera Kresadlova and children to France. After several months spent in the French capital Vera decided to return back to Czechoslovakia, and Forman decided to conquer America.

Greenwich Village

Forman rented a house on Leroy Street in Greenwich Village, New York with Ivan Passer (who had decided to emigrate immediately after the occupation). Forman still recalls those times with pleasure: “We never refused anyone who wanted to come in, so crowds of people were coming back and forth. Some friends from those days have stayed, some are gone, but still there might be some who left just for a minute and now they are looking for the way back. The playwright John Guare (responsible for the play The House of Blue Leaves) says that on entering the house he always felt he had left America and arrived in avant-garde Bohemia – the land, where only what you read and what you drink really mattered.”

Forman finished the screenplay for Taking Off (1971) with a help of a young American filmmaker named John Klein. During shooting, he met his future producer Michael Hausman. “You could have seen immediately that he was a wonderful person. He was riding a motorcycle to get to work. He was connected with underground movies and he was able to fit a film into any budget whatsoever. He probably would have been able to start pick pocketing, if it had been necessary for a film. And yet, his family belonged to one of the wealthiest ones in New York," recalls Forman. But the film Taking Off wasn’t really successful. „My instincts of a filmmaker were too Czech and I didn’t have any experience with American films. Making films about the true life around us, which I hadn’t known at all, was pointless. But it happened, so I can say the last Czech film of mine was made in New York. Since that time I have been making only American movies.”

Hotel Chelsea

After the commercial failure of Taking Off, Forman had to start from scratch. He moved into the Chelsea Hotel; supposedly he had only one dollar a day to live on, which he spent on one can of chili con carne and one bottle of beer. Despite this, he never considered returning back to Czechoslovakia. When his agreement with Paramount Pictures ended he became an official émigré. Forman recalls,” I was waiting for an offer which could change my life but in the meantime I jumped for anything that promised at least a free lunch.”

Forman took part in a documentary about the Munich Olympic Games called Visions of Eight (1972).During the Olympic games, he witnessed the tragic Palestinian assassination of the Israeli sportsmen.

Forman also managed to fulfill one of his dreams - to stage a play on Broadway. The Little Black Book was a comedy written by his friend Jean-Claude Carrier,

He also tried working in the American advertisement industry and directed a commercial for Royal Crown Cola. The concept of this advertisement was based on the opening sequence of his film Taking Off. As Forman recalls, “I realized then that absurd, Kafkaesque things were happening in American democracy as well as in the bureaucratic communism. The full length film had cost 810 000 dollars but its one minute retread swallowed a whole million.”

During this time, Forman began his friendship with his now-agent Robert (Robby) Lantz. Robby’s clients included Tennessee Williams, Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton and Leonard Bernstein. They met during Forman’s first stay in New York. “I have to admit that I wasn’t sure with it at first. Robby had been representing people all America was more than familiar with but still he treated me as if I was the most important person in the world. It took me a while to recognize that it wasn’t any kind of trap but Robbie’s normal behavior. For instance, he never wanted me to sign anything for him. Once we made an agreement and since that time we can both rely on that.”

The First Academy Awards

In 1974, Forman was given a second chance to make an “American” film. Actor Michael Douglas and independent producer Saul Zaentz sent him an offer to direct a film adaptation of Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. Later, Forman learned that Michael’s father Kirk Douglas had already sent the same offer to him in the 1960’s. It was probably confiscated by the secret police, because it never got to Forman. Nonetheless, the film One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) was a huge blockbuster and received Academy Awards in all the main categories.

Forman became a successful American director almost overnight. He was offered many tempting films, but what he really wanted to direct was the musical Hair (1979). Even though the musical wasn’t as successful his pervious film, it wasn’t a loss, and Forman’s position as a renowned director was solidified.

The 1980s

Italian producer Dino Laurentis offered Forman a film version of E.L. Doctorow's bestselling novel Ragtime (1981). Forman’s old friend Miroslav Ondricek worked as a cameraman on the film. They also worked together on Forman’s next picture Amadeus (1982). Filming Amadeus gave Forman the rare opportunity to return to his homeland. Although he was an American citizen, Forman was never able to receive official permission to visit Czechoslovakia. To solve this problem Forman called Jiri Purs, head of the Czechoslovak Film Institute and the “boss” of the whole Czechoslovak communist film industry. He explained to Purs how much money American filmmakers were willing to spend in Czechoslovakia, and quickly obtained all the necessary visas. Filming was heavily controlled by the secret police. The picture was nominated for eleven Academy Awards, and was awarded eight.

Following Amadeus, Forman started pre-production on another historical drama – the film adaptation of the famous 18th century novel Les Liasions Dangereuses written by Choderlos de Laclos. Due to the misunderstanding with the author of the theatre version, the playwright Christopher Hampton sold his rights to British director Stephen Frears. Therefore, two different versions of the same novel were made at the same time: Forman’s Valmont (1989) (based on the original novel) and Dangerous Liaisons (1988) (based on Hampton’s theatre adaptation). Unfortunately, Valmont’slate release caused the picture’s commercial failure. As Forman recalls, “Normally, such a result would have caused depressions and lethargy in me but in those days there was something completely different I was interested in: the communist regime in Czechoslovakia was over and Vaclav Havel, my former schoolmate and friend, had become the President of a new, democratic Czechoslovakia.”

The President’s Visit

In February 1990, Milos Forman met Vaclav Havel in New York City after the newly elected President of democratic Czechoslovakia made his legendary speech to the American Congress. Afterwards, the two (with bodyguards) went on a private tour of the city. Vaclav Havel wanted to go to Washington Square, the famous meeting place of young people and bohemians. According to his bodyguard, Washington Square Park was not a safe place for a President. Havel joked with Forman:” How come I could be shot? I’ve just left Bush and he didn’t mention that you are at war at all. When did it start?” Forman responded: “I haven´t a clue, I haven’t seen the news today. The amused President asked: “Is there anything Czechoslovakia could do to help the United States?" He proclaimed that Czechoslovakia was not going to interfere with U.S. foreign policy, and he was going to prove it by taking a short walk around the block.

Forman remembers his recently deceased friend: “He was still the same boy I used to know, sometimes even childish maybe. But he was so clever, intelligent and he had a great overview of all the things going around. But still the same boy…We saw each other every time he visited the USA and always when I went to Prague. But most of the time we were talking about our friends from Podebrady. Never about politics. Or almost never.”

The Third Marriage

Towards the end of the 1990s, Forman met his third wife Martina, a student at the Film Faculty of the Academy of Arts in Prague. She asked him to help with her graduation thesis, which was a comparative study of Czech and American filmmaking. According to Forman, “Her polite letter reminded me - my older self – of the times when I was just a young man, who didn’t pay respect to the order of this world, when I offered my screenplay to Charlie Chaplin, who was residing in Switzerland then. And I really had hoped that Chaplin might be attracted by an offer from an unknown director from Stalinist Czechoslovakia, who hadn’t achieved anything at all yet. So I decided to meet that girl. I expected an intellectual girl with glasses and sweater too loose for her, but an elegant blonde came instead. She was tall and slim, and I remembered that I had seen her before. That had happened years ago, and even though we hadn’t said a word then, I knew very well that I had liked her from the start.” In 1998 their twins Andrew and James were born and a year later Milos and Martina were married.

1990s and today

Forman’s next film The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996) received a scandalous reputation. The film was based on the life story of porn magnate Larry Flynt, and told an impressive story about freedom of speech and the First Amendment. Despite positive reviews the film was blemished by a negative campaign led by an American feminist group that was offended by Forman’s championing of Flynt.

After the failure of his film Embers(Embers, 2005) starring Sean Connery, Forman and Carriere started working on another project. Forman’s last feature film is a historical drama about the Spanish inquisition and painter Francisco de Goya called Goya’s Ghosts (2006). Another film was planned; Ghost of Munich, but the shooting was abolished due to the production problems.

In 2007, Milos Forman returned to work in Prague. Forman staged a jazz opera called Dobre placena prochazka (The Walk Worthwhile) (2007) with his sons Petr and Matej at the National Theatre. He raved about working with his sons: “Yes, we did argue, but about the details only. Someone must be the one who has got the last word, and I guess it was respect, which had won. But respect from both sides, I have to say. They were a little bit afraid of their father, of course, as they had remembered me with the switch still, but I did respect them as well – they are experienced theatre makers and have a wonderful imagination. The advantage was we were three to argue. Two had always united against the third one, no stale mate situation ever happened.”

He is very proud of the success of his older set of twins, who have become respected theatre makers in Europe: “I always come to see their performance, whenever I can. I’ve seen everything so far. They are really smart, my boys, I’m really proud of them.”

Milos Forman filmed a performance of Dobre placena prochazka (A Walk Worthwhile) (2009). When it was released at the International film Festival in Karlovy Vary, the almost 80 year old director said: “Ask me anything you want to, take pictures of me whenever you want to, I do not care. But please, don’t push me for a walk anywhere, I’m little bit too old for such things,” as he lit up his cigar. He claims that he is not preparing any other projects: “No more films, I’m on holiday.”

Of course “next time it is going to be even harder.” But who knows?